James Long’s “The Lives She Left Behind”

I did a little bit of cheating this week. Well, I don’t know if it really was cheating, but I do at least have to make an admission.

As a matter of pride, personal principle and/or obsession, I have certainly endeavoured to treat all the dear English counties equally throughout this challenge and remain steadfast to my own rules, namely to read:

- one book per county

- written by an English or England-based author

- and first published during or after the year 2000.

The fact that I’ve actually read two novels for this week’s county may then pose a slight ethical problem on the face of it, but don’t worry: I have my reasons and, you will be immensely relieved to know, there will only be one review. And no bias or favouritism. Phew.

The problem I faced with Somerset was that the book I really wanted to read…really, really wanted to read…and which was recommended to me by a fellow English Literature graduate from the University of Warwick specifically for this Place-and-Space-oriented challenge (and therefore, I trusted, bound to be rewarding) was Ferney, by James Long, first published in 1998. Doh. However, well aware of the trauma and chaos this would wreak in my simple mind, my dear university colleague also offered me a timely olive branch: Ferney has a sequel, published in 2000, called The Lives She Left Behind.

“Ferney”, the prequel to “The Lives She Left Behind”, by James Long

You see, me being the way I am, I am absolutely incapable of reading any book if it is not the first in a series. I physically recoil from diving in at number 2/3/4, no matter if the stories would make complete sense as stand-alones or if all the preceding novels were poorly received of no interest to me. If I wanted to read the 10th Inspector Morse mystery or the 20th Poirot novel, or the 50th account of the Fifty Shades of Grey (oh the horror) I’d have to start from number 1. The same goes for film and TV series and even some music albums. I realise it’s an unhealthy and pointless compulsion, but my physical and mental aversion to not being privy to the entire context of something is all-consuming, which is why I was left trembling and practically rocking in a corner of the classroom when, during my degree, I was asked to watch Series 6 of 24 as part of an American cultural studies module. I had to watch 144 hours of the damn thing (all the way from series 1 episode 1) in just over a week. Boring and expensive, let me tell you.

So it was with these James Long novels. On Sunday, Monday and Tuesday, I found myself working my frantic way through Ferney so that I could focus my attention, in good conscience, on The Lives She Left Behind for the rest of the week. I’m glad I did this, it turns out, because the latter definitely continues the story of the first and, I feel, wouldn’t have made much sense on its own. So, to set the scene…

In Ferney, the reader meets Mike and his nervous, haunted-by-the-past wife, Gabriella, nicknamed Gally. Filled with love, tenderness and concern for her, Mike still does not fully understand the mystery behind Gally’s nightmares or why she develops a sudden, desperate attraction to the Somerset village of Penselwood which they happen to pass through in the car one day, while venturing away from their home in London.

In this tiny, historic village, Gally is drawn to the abandoned, run-down Bagstone Cottage; at her urgent and startling insistence, Mike agrees to buy it and move in, hoping she has finally found something to bring her out of her depression. Over the course of the novel and the cottage’s gradual refurbishment, Gally’s nightmares subside – even stop altogether – and she finally seems to be at peace in the landscape around her. However, soon there is revealed something distinctly troubling and, to Mike, dangerous, about an eighty-year-old man who persists in loitering around Bagstone Cottage and Penselwood’s many lanes, and who seems to have a familiar relationship with Gally. This old man’s name is Ferney.

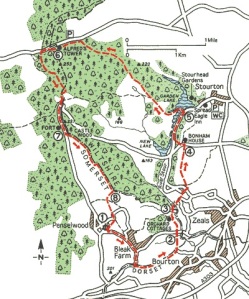

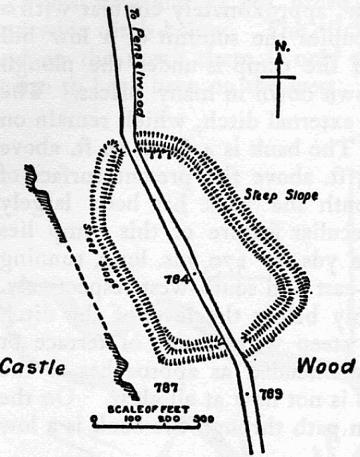

A plan of King Cenwalch of Wessex‘s fort in Penselwood, believed to be the site of the Battle of Peonnum (between Saxons and Britons) around AD 660

Ferney opens Gally’s eyes to a past she never knew she was part of, spanning millennia. With his encouragement and, eventually, of her own accord, Gally starts to remember that she has always lived at Bagstone Cottage and in Penselwood; that she has always known Ferney; that she has lived many, many lifetimes by his side, both of them in different bodies, at different ages and from varying backgrounds, but always drawn home to each other’s arms.

The remaining banks and ditches of King Cenwalch’s Saxon fort in Penselwood.

Mike is left, disbelieving and heartbroken, on the sidelines, but the reader is carried along on a timeless love story that incorporates swathes of history and vast stretches of the Somerset landscape. It is a love story of people and of the land. It is supernatural (which I normally hate; God knows I hated The Time-Traveller’s Wife) and yet somehow its connection to the landscape – its paganism – transforms it from what might be nonsense into an epic. That is not to say it is a difficult read; it is most certainly not. It’s an ideal combination of Hardy’s glorious Wessex novels and a more usual romantic summer read.

King Alfred’s Tower (1772) near Penselwood, believed to be built on the site of the ancient Egbert’s Stone. This stone was the mustering place for Alfred the Great’s troops in AD 878 when they were preparing to fight the Danes/Vikings.

If I was reviewing and rating Ferney, I’d give it 4/5 stars for Long’s originality, characterisation, depth of historical and geological research and overall writing style that so ably combines past and present, fate of people with fate of land. But of course, I’m not reviewing Ferney because it doesn’t fulfill by my challenge’s criteria. For this challenge, I’m concerned with rule-abiding, year-2000-published The Lives She Left Behind. For that, I put Ferney entirely out of my mind.

It is, however, difficult to summarise the plot of the sequel, set a few years later, without giving away what happens at the end of Ferney. I don’t want to do that as I think, of the two, Ferney is the one most worthy of reading. Let me just say, then, that the time-span, love-story premise continues in much the same vein, with the same general characters, in Long’s second and final novel in the series.

It is just as much about being physically and emotionally connected to the Somerset landscape:

“as the blade touched the earth, he snatched his hand away as something travelled up through it, through his fingers and up his arm […] He reached out again that there it was, flowing through him, a flood of light and peace and knowledge and something startling that felt like love” (73)

It is just as much about spanning time, unearthing history and rooting through “the ploughed-up soil of the past” (330):

“His tour continued back and forth through the carnage of plagues, rebellion, the brutality of purges pagan, Catholic and Protestant as he circled the village, soaking up the sight of it now with eyes which mixed with older times, blending in its history” (136)

It is just as much about discovering one’s “deep familiarity” (216) with people and places:

“it was not like learning, not quite like remembering – more a matter of unforgetting, knowing how to see what was already there, bringing back a confidence in how to be” (136)

It is also just as pagan and just as much a love story, and written in the same capable style.

The remains of one of three the Norman motte and bailey castles near Penselwood, dated after the Norman Conquest of 1066. This one is known as Ballands Castle and shows the village was of strategic importance to William the Conqueror.

The thing that instinctively makes me rate The Lives She Left Behind lower than its teammate despite all that good stuff, is that the novelty of Long’s concept has somewhat worn off. In its pages, the beauty and drama do not shine as brilliantly or unexpectedly as in Ferney, precisely because they are not as brilliant or unexpected. The characters that are new to readers are not as engaging as those in the first novel, and nor do we learn anything revolutionary about the characters we recognise, as everything of importance has already been told. In fact, due to this repetition, it sometimes seems as though (like so many Hollywood endeavours) Long’s second novel is simply a not-so-good rehash of the first, with a few tweaks and a younger cast. If I had read The Lives She Left Behind without reading the other (for the sake of ethicality, I am judging this novel in a vacuum) I wouldn’t have been blown away by it: hence the rating of 3/5 stars.

In terms of what light the novel shines on Somerset itself, its sweeping hills and dales are painted beautifully and mystically. So much so that I’m desperate to revisit the area and just walk, walk, walk all over it, taking it in. As I said, Long writes with hints of paganism and, as a result, frustration with the encroachment of human authority on the fertile landscape is a key theme in every page of both novels, but is emphasised more noticeably in Lives where, interestingly, there is far greater human presence on the hills. Human intervention on nature shows through from the early years, when church bells started to measure and dictate time across the fields, to the present day when the horror of the Ordnance Survey means that “a concrete lump” (256) has been added to a favourite hilltop as a navigational marker. The aim seems to be “to measure the whole country, to pin everything down to the nearest inch […] Everything’s mapped. People are mapped” (256). Even the careful archaeologists who aim to do as little damage to the landscape as possible end up making a mess. Overall, in Lives, the landscape is presented as harshly colonised; we notice the effects of modernisation so much more, even though only a few years in Long’s setting have passed since Ferney. Imagine then, Long seems to say, how much damage humans will do in decades or centuries.

Another key theme throughout Long’s version of history, particularly prevalent in Lives, is a somewhat political one: the contention between the ‘official’ or documented past (Kings and Queens, significant battles and famous painters) and the reality experienced by ordinary people who were/are separated from authority:

“We let the wrong people tell our story for us, don’t we? The newspapers, the TV news, history books are all the same. We let the big egos tell us about the wars and the business deals – all the testosterone stuff. We let the drama enthusiasts tell us about the disasters and the tragedies and the accidents and we end up thinking that’s what the past is, that’s what the present is, that’s what our country is, but it’s not […] Mostly, it’s a lot of ordinary friendly, generous people over a very long time, doing the best they can in a quiet sort of way […] We shouldn’t let the people take charge who want to be in charge. They’re the last ones we should trust” (337)

Whether or not we can absolutely trust Long’s novels to accurately represent ordinary working-class lives throughout history is almost unimportant; this is a love story after all, about people and about landscape, and about neither of those having changed very much – if you take the time to block out modern distractions and to look carefully – since the dawn of time.

Author James Long, according to his bio a former BBC correspondent and writer of historical fiction, thrillers and non-fiction.

Next week I’ll be reading The Forest by Edward Rutherford. It looks like another landscape epic!