David Dabydeen’s “Our Lady of Demerara”

I couldn’t resist picking David Dabydeen’s Our Lady of Demerara to represent the West Midlands in this literary journey – although I never met him, and wasn’t even aware of him until researching this novel, Dabydeen is a Professor at the Centre of British Comparative Cultural Studies at the University of Warwick, my alma mater. Not that I’m biased or anything. And although it was tough-going at times, the novel is a perfect choice for a challenge that wrestles with the issues of place and space.

Lance Yardley, aged 30, is desperate to cut his ties with the working-class council estate he was brought up on: Albion Hill, in rough and seedy Coventry. He seeks escape through his work as a (failed) writer, through his (dysfunctional) marriage to middle-class actress Beth, through trawling the backstreets of the grimy city for prostitutes, and, eventually, by travelling across the world to Guyana on the trail of a dead Coventry priest who was once a missionary there, and in whose memoirs Lance urgently searches for the meaning of life. A strange progression of events, but this is the journey of someone rootless, in turmoil and very possible insane.

Prof. David Dabydeen of Warwick University

It is not only Lance’s relationship with his lot that seems to have cracked; this novel problematises all relationships, including those between family members and spouses; between different classes and races even living in the same neighbourhood (Lance labels his own wife “’a bourgeois empty-headed cunt’” [13]); between England and Guyana, with a colonial legacy that has left the latter in a shambles. Everyone is separated by prejudice and ignorance; Lance is a man torn apart, in a world torn apart. It seems fitting that he journeys to Guyana, where “slavery done two hundred years now but the Negro still feeding on the past. He too lazy to make effort for the present and the future, so he save up the past like a hoard of saltfish, and when he chew his mouth go sour and he spit” (77). Lance is shown to feel the same obsession, hatred and resentment for his own history. These are emotions that abound in this novel.

But let’s get back to the beginning.

Dabydeen presents a hellish view of England, which suffers from “incredible cold […] grime” (53), “ignorance and spite”, where the only spiritual connection is with “the high-street shop” (54). Coventry itself seems post-apocalyptic, with “houses joined to each other in an endless march of bricks […] asphalt, metal” (255), interspersed with “burnt-out shells […] and the crowded graveyards [which] were testimonies to the German bombing” (64-5) of the Second World War. The air is filled with the “hideous rumble of wheels, the hollering of drivers” (256) and the whole place feels like “the ending of the world” (105).

The ruined shell of Coventry Cathedral, bombed in WW2, still stands today.

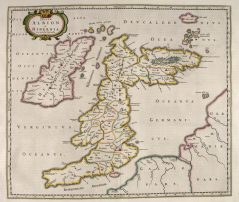

In amongst this mess is the drab council estate, Albion Hill. ‘Albion’, the ancient and poetic name for Great Britain, is an ironic title for this district in which there is no sense of national pride or belonging, or affinity with those “posh gits”, “the ones with suits on and secretaries in offices” (40) who run the country whilst maintaining wilful ignorance of the working classes’ existence. The notion of ‘Britishness’ means nothing to the residents; they have abandoned it as it has abandoned them.

Not only does Lance feel disconnected from Britishness, but from the rest of his family and his neighbourhood too. His lack of belonging is a product of his childhood – during which time his mother walked out, his father (now dead) was imprisoned for theft and he was shifted continuously between foster families – as well as his ambition; he wants more from his life than “what every child in Albion hill aspired to – a council flat and the dole, the income boosted by a little burglary, a little trade in stolen goods, a little job on the side cleaning, plastering, decorating” (28). He is ashamed of his class, of “the cultural desert” (15) he lives in, of being “a local born and bred” (14) when others around him can boast such “exoticism” (45). His wife Beth treats her Indian heritage flippantly because her past is “utterly irrelevant to [her] life” (14); Lance is filled with envy, anxious to define roots for himself that mark him out from others, to which he belongs so completely that he can exclude her.

‘Insulae Albion et Hibernia’ (Islands of Great Britain and Ireland) from the 1654 Blaeu Atlas of Scotland

Suffering with “maimed wing and spirit” (121) without a proper family history on which to prop his existence, Lance goes on the hunt for “a moment of vision” (9), “wholeness and transfiguration”, a means to cleanse “his life of the accretions of Coventry dirt” (110) and give himself “depth” (93). His spiritual search does not get off to an auspicious start, ironically beginning on the streets of Coventry looking for a prostitute called Corinne. Indeed, no matter how far he travels away from it, the reader feels Albion Hill “in his shadow and his conscience” (68), recognising all his efforts as being “thwarted, unfulfilled” (69).

Ultimately, the only way Lance can discover his desired identity is to imagine it, to surround himself with a fictional version of the past and of his roots, to convince himself that he has found his home and his heritage. The life of the priest, Father Jenkins, is the key to the re-conception of Lance’s own life: through blending himself with the priest in his letters home, Lance makes himself believe in his own significance and value in his community. As though playing dress-up, Lance takes on a sudden spirituality that allows him to boast of inner “peace” (260) and present his transformation as a Christian reincarnation. Ironically, his fictional concept of self at the end of the novel, made up as it is of odd parts of other people’s lives and containing very little truth, is more severely jeopardised than ever.

At once, with Lance’s creative power over his story realised, the narrative of Our Lady of Demerara is thrown into chaos for the reader; if it was fragmented and confusing before, here is where it gets really mind-bending.

“My priest’s story was broken and haphazard. Cryptic lines. Gnomic paragraphs. Obscure notes. Doodles. Impossible puns. I would mend the sentences, make them flow, give them purpose and direction. I would design his life and where there were holes and gaps I would conceive of incidents and themes. My landfill would be my imagination but I would draw too on actual people I knew, give them places in the story. [They] lived ordinarily, purposelessly, even stupidly. I would revise their existence on the page, or originate a new existence for them […] If, because of my superior education, I owed them anything, then it was to rewrite them” (93).

- If Lance is recreating his own life, what else in the novel is subject to his alterations?

- Are the characters, Dabydeen’s creations, actually presented through Lance’s transformative eyes? Is Beth really so middle-class, is Miriam truly acceptant of her Albion Hill lot, or is that just how the frustrated Lance sees them?

- Is this a novel with a frame narrative, and does the pervading authorial voice belong to Lance, and not to Dabydeen, as we assumed?

The reader begins to question their assumptions of ‘truth’ behind the narrative when it is revealed to be mediated by Lance, who is so hungry to reinvent everything and everyone around him, who admits to fabricating and “caricaturing” (46) people in his letters and plagiarising sentences from Jenkins’ memoirs, “purged or reinstated in different forms” (51).

Aeneas, the hero, flees Troy with his father on his back and his son at his side: 3 generations with hope of a new civilisation. This is unlike the rootless Lance, who leaves his family behind.

The effect is disorientating, alienating and, because of this, hugely successful. Lance is thoroughly unlikeable because of his cruel treatment of others – especially women – and seedy pastimes, and yet we are made to feel as disappointed by the state of the country and humanity as he is. We are guided, bemusedly and against our will, to Guyana on the will of his unhinged character and challenged to follow his incoherent, tortuous and, at times, dull review of his existence to a solution that fails to satisfy us – or the rest of the characters – because of its foolishness. And yet we follow it and this anti-hero, and pity him, because it is a kind of poetry; an agonised, filthy poetry.

I would go as far as to say that Our Lady of Demerara is the modern Aeneid, detailing Lance’s odyssean journey across oceans to develop a mythology on which to base his identity and to find a new home away from Beth, who is the Dido weighing heavily around his neck. But Lance’s quest ends in nothing; there is no promised land. Unlike Aeneas, Lance is not a hero; he is misogynistic, dishonest and corrupt. Nor is he sailing towards Albion, to a place where he can found a new Britain to be proud of; rather, Albion Hill, and Britain as a whole, is the ravaged and ruined land, like Troy, that he is leaving behind. Britain certainly is presented as ruined in this novel, guilty of a greedy colonial past, damaged by decades of war and capitalism, and plagued by a complete lack of unity among its immoral inhabitants. Britain is worthless, this novel seems to say; it has no future except further decay.

Aeneas recounts the ruin of Troy to Dido. Painting by Pierre-Narcisse Guérin, 1815.

Overall, this was a novel that to read was not always pleasant but constantly impressive. Its characters were hard to relate to and barely developed, but that was the point. The narrative was nonlinear and fragmented but that was the design. The plot was slow-moving and unbelievable but it could have worked in no other way. It was epic, artistic, intelligent and truly awesome. I’ve never struggled for so long to decide on a rating for a book: if I was still at university I’m sure I would have rated this a full 5/5 for its sheer scope and literary achievement, but here, back in the real world, I tell myself reading pleasure has to count for something. Phenomenally constructed but hardly loveable for its bleakness, finally, 4 stars go to Our Lady of Demerara.

Next week I’ll be reading The Bellwether Revivals by Benjamin Wood, set in Cambridge. We’ve almost reached the halfway mark!

DABYDEEN, David. Our Lady of Demerara. Leeds: Peepal Tree Press Ltd, 2009.

Featured Image: Breugel’s “The Burning of Troy” c.1621