Eva Ibbotson’s “The Dragonfly Pool”

When I was young – around the 8 or 9 mark – my absolute favourite book for a long time, and over very many readings, was Eva Ibbotson’s Journey to the River Sea. I remember this vividly, as I remember clinging to the book’s pages and several of its characters vividly, but the actual detail of the story I have long since forgotten. Or so I thought.

Looking up plot summaries of it recently, I am astonished to find how much of the story strikes chords in the depths of my memory: English orphan Maia is sent away to long-lost and unpleasant relatives in the Amazon region of Brazil, where she meets and adventures with several other children – both Amazonian and European – before they join together to carry out their escape from their discontented lives. I am secretly pleased to recognise even at that age my passion for books about far-flung journeys and other cultures. And perhaps the plot had a subconscious effect on me too, before I reminded myself of the content of the story: I’ve just married my very own Brazilian, after all, having fallen in love with both him and his country!

Anyway, when I was researching books for this challenge last year, and saw that another of Eva Ibbotson’s children’s books, The Dragonfly Pool, met my conditions for the county of Devon, I absolutely couldn’t resist. There are a great many similarities between the plotlines and characters.

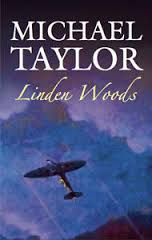

Eva Ibbotson’s “Journey to the River Sea”, one of my childhood favourites and winner of the Smarties Prize in 2001

The Dragonfly Pool begins in London, just before the outbreak of the Second World War. Precocious, young Tally Hamilton lives happily in the city with her loving father, a respected doctor, and her aunts. However, when Mr Hamilton is offered a scholarship, by a grateful patient, for his daughter to attend a fine boarding school in Devon, his concern for her safety in the impending war overrules his desire to keep Tally near him. Although initially resistant to the idea of leaving behind all she knows and loves, Tally is sent off by train to the relaxed, fun-loving, if “strange and slightly mad” (62)

Delderton Hall. And she grows to absolutely adore it, falling in love with its unique natural surroundings, so different to what she had been used to in the city:

“There was no lovelier place in England: a West Country valley with a wide river flowing between rounded hills towards the sea. Sheltered from the north winds, everything grew at Delderton: primroses and violets in the meadows; campions and bluebells in the woods and, later in the year, foxgloves and willowherb. A pair of otters lived in the river, kingfishers skimmed the water and russet Devon cows, the same colour as the soil, grazed the fields and wandered like cows in Paradise. But it was children, not cows or kingfishers, that Delderton mainly grew.” (35)

Although the novel unfortunately does not provide much description of Devon, the county is set up as a safe and romantic backdrop where freedom reigns and children flourish. Against its green countryside, “it was easy to forget […] that Britain and France and so many of the free people of the world were in danger. Here in Devon we were unlikely to be bombed […] but we must be ready to do everything to help the war effort if the worst happened” (54). Domestic staff are being called up, radio broadcasts talk gravely about the political situation, and picture-houses show newsreels featuring Hitler’s fearsome visage and harsh foreign commands.

But Ibbotson does not tell a Blyton-esque story of a boarding school’s efforts to withstand the war; she instead catalogues the children’s adventures around the grounds and on an overseas school trip to a folk-dancing competition held in the central-European Kingdom of Bergania (a Kingdom also beset by but so far proudly resisting Hitler’s threats). Soon, this develops into a mission to rescue the orphaned and mortally endangered Prince of Bergania, a modest and lonely boy called Karil. It is all slightly bizarre, but lives up to themes I recognise and appreciate of Ibbotson: themes of foreign journeys, children’s decision-making and agency, and of the hills and valleys of Devon (and Bergania, for that matter) being just as part of the children’s lives as their friendships.

I enjoyed the book, but I think that even had I read it at age 9, it would not have captured my imagination quite as much as Journey to the River Sea did. In truth, I was disappointed that the plot and setting were not more original – I wonder what percentage of children’s books are based around their antics during boarding school life…80%? 90? – and even with a couple of mentions of the impending war, the folk-dancing set-up in Bergania seems too trivial and far-fetched to give credit to Tally’s determination to attend and to rescue Karil.

I simply did not connect to the characters or to the landscapes that Ibbotson creates here. Part of the problem is that Tally, for one, is entirely confident and level-headed; she is not a sympathetic character, or one in need of her friends’ or a reader’s support in overcoming the obstacles set out in front of her. What is more, the obstacles – whether German officers or cruel, stuffy Englishmen or the challenges of war itself – hardly seem to faze the children in their exploits. Everything seems a bit too easy to overcome. I really think Ibbotson is missing a trick here; unlike in Journey to the River Sea, there are no vulnerabilities in the characters or challenging moments in the plot that young readers can catch hold of, be gripped by or dwell on; there is no chance to will the protagonists onward in their struggle because, before you know it, they’ve succeeded in another aspect of it. Overall, as a child or as an adult, I rate it 2/5 stars.

This novel certainly has not put me off Ibbotson, however. I look forward to reading some of her other work – aimed variously at children, young adults and adults – whilst knowing that it is for Journey to the River Sea that she received most critical acclaim, winning the Smarties Prize in 2001 and being highly commended for the Guardian, Carnegie and Whitbread Awards. I am truly sad to learn that Ibbotson died in 2010, and feel that I should have known this at the time: it is like losing a childhood heroin.

Next time I’ll be reviewing my very last book ever for this literary challenge around England! It’s Proper Job, Charlie Curnow! By Alan M. Kent, a Cornish writer. Stay tuned for that, as well as my subsequent summary of my favourite books and lessons from the whole year of reading.