In the past couple of weeks I’ve read novels from Dorset and the Isle of Wight (review to follow), counties which often epitomise the idea of the English seaside holiday, where there are “rock pools rather than hot sun, seaweed rather than find white sand” (Webb, 53). Of course, these novels would not have been hugely interesting if they had not challenged this stereotype – and challenge it they did. “Holidaymakers – there were always some” (Webb 46), one character notes, but there are also those who are always unable to leave.

Katherine Webb’s “The Half-Forgotten Song”

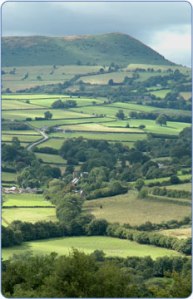

First of all, I read Katherine Webb’s Dorset-based tale, The Half-Forgotten Song. You may remember that I very much enjoyed The Legacy by the same author earlier in the year, and I was not disappointed by my second foray into her work. Much like The Legacy, in fact, this story is made up of two narratives: one situated in the past (memories of the now elderly Dimity Hatcher from several childhood summers) and one in the present, with writer and art-collector Zach revisiting the village of Blacknowle in Dorset, meeting Dimity and uncovering her history for the very first time. Both narratives revolve around one man: the artist, Charles Aubrey.

Zach’s life has gone a little to pot recently: his relationship has broken down; his young daughter Elise has been moved abroad by his ex; his small but precious art gallery in London is dwindling into obscurity; and although he has already drained his publisher’s advance, he just cannot find the time, motivation or material to complete his book on the subject closest to his heart: the life and work of famed 20th century artist Charles Aubrey. That is, until his publisher warns him that a competing writer is close on his heels with a book on the same lines, and Zach realises he had better get a move on.

Zach is desperate to find a new slant on the oft-told story of Aubrey’s life to feature in his book. Who are the mysterious, unknown faces in his paintings? Is any one of his apparent succession of mistresses still alive to tell her tale? Why did Aubrey choose to return with his family, year-after-year in the 1930s, to the same tiny, beachy village of Blacknowle? Possessed by these unanswered questions, Zach shuts his gallery and journeys westward to Dorset, to see if anyone still remembers the artist, and can provide any answers.

To his profound astonishment, it isn’t long until he stumbles accidentally across the real-life, wrinkled Dimity Hatcher – the beautiful ‘Mitzy’ that features in many of Aubrey’s paintings from the period, as well as his so-called mistress. Now, hidden away from the world in her cottage, presumed dead by all other Aubrey-philes, timid Dimity is haunted by her own demons. Zach works painstakingly and tenderly to gain her trust and extract her secrets – but will the truth end up helping or hindering him? Will Zach’s city-born belief that “it’s kind of restful, being surrounded by landscape, rather than people” (160) stand up in the face of Dimity’s pain?

It is through Dimity, most of all, that we get a view of the county’s landscape and outlook. Whether as an old lady or as a poor, fourteen-year-old gypsy scavenger in 1937, Mitzy is absolutely tethered to her locality:

“There were roots indeed, holding her tightly. As tightly as the scrubby pine trees that grew along the coast road, leaning their trunks and all their branches away from the sea and its battering winds. Roots she had no hope of breaking, any more than those trees had, however much they strained. Roots she had never thought of trying to break, until Charles Aubrey and his family had arrived, and given her an idea of what the world was like beyond Blacknowle, beyond Dorset. Her desire to see it was growing by the day; throbbing like a bad tooth and just as hard to ignore” (193).

It is Aubrey who awakens her to the idea of what exoticism might lie outside of Blacknowle. Morocco, where the family also holidays, is as far away as Mitzy can possibly imagine – and she can imagine no further away than “Cornwall, or even Scotland” (113). Each year, as the family comes and goes from the village, Dimity becomes more and more conscious that she “had remained the same, static” (229). But while she sees them with respect and through awed eyes, they envisage her as the embodiment of Dorset simplicity, ignorance and mythical “old magic” (194). In her naivety, she is flattered by Aubrey’s wish to use her as his muse, failing to realise that he will never adore the subject of his paintings as much as she adores him.

Eventually, as the story unravels, Mitzy comes to realise that while Aubrey appreciates her precisely because of her place in the ancient and natural landscape, it is the landscape that also traps her, inhibits her and, in her old age, terrifies her:

“The wind was so strong […]. The gale tore around the corners of the cottage, humming down the chimney, crashing in the trees outside. But louder than any of that was the sea, beating against the stony shore, breaking over the rocks at the bottom of the cliff. A bass roar that she seemed to feel in her chest, thumping up through her bones from the ground beneath her feet […] The smell of the sea was so dear, so familiar. It was the smell of everything she knew; the smell of her home, and her prison; the smell of her own self” (1-2).

This is a novel about beautiful, terrorising landscapes that are adored by some and loathed by others. It is also a novel that encourages my good opinion of Webb for the way it is written and its suspenseful tone, although the profound, relatable characters present in The Legacy were unfortunately not as present here – I suppose largely because they were either distinctly unlikeable (Dimity) or downright average (Zach). Webb does balances the plotlines between past and present effectively, so that both engage the reader and build tension. In some places, however, I thought the pace could have moved things along quicker – it did occasionally drag. In terms of personal preference, I did not enjoy the subject of the story quite as much as I did The Legacy. Indeed, at certain points I did feel slight irritation that some memories seemed quite contrived or unrealistic – I did find myself thinking such things as ‘she wouldn’t really remember that – it’s only in there to tie up a loose end of the mystery’. So some of the narrative ‘weaving’ could have been more natural. But overall a good (half-forgettable!) book, so 3/5 stars.

As mentioned, I’ll shortly be reviewing the Isle of Wight novel Wish You Were Here by Graham Swift. Stay tuned!

WEBB, Katherine. A Half Forgotten Song. London: Orion, 2012.

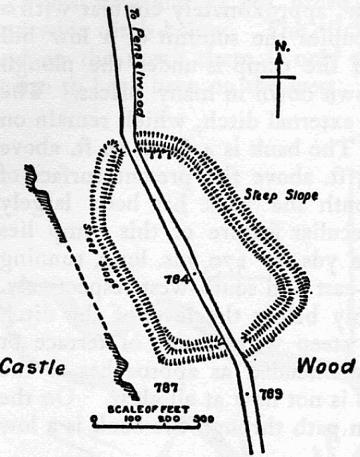

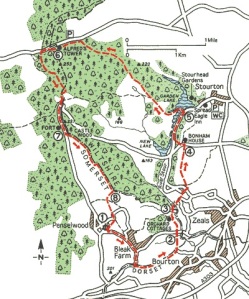

Featured Image: Ghostly Tyneham, a deserted village in Dorset, near to fictional Blacknowle where the novel is set. It was taken over by the war office in 1943 for military training and never returned to the locals.

http://www.flickr.com/photos/37801007@N07/4875435993/