This week I read Annabel Pitcher’s My Sister Lives on the Mantelpiece which is set in Cumbria. Throughout the novel there are several explicit references to the characters’ Lake District environs, on top of which the protagonist lives and attends school in Ambleside, plays football against nearby Grasmere and takes trips to coastal St. Bees – all of which are real Cumbrian towns.

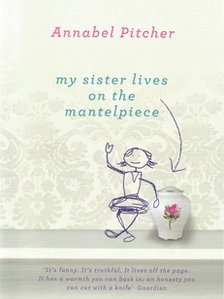

“My Sister Lives on the Mantelpiece”, Annabel Pitcher

It turns out I did not have a lot of choice when it came to modern books set in Cumbria; despite plugging my List at every possibly opportunity, this northern county has remained relatively under-represented in suggestions for this challenge. That being said, Pitcher’s fantastic debut – which also, rather aptly, deals in part with issues of under- and misrepresentation – might well have been my first choice in any line-up, despite being yet another so-called ‘children’s book’.

Perhaps because I’ve spent almost all of my educational life reading novels about Victorian aristocrats or epic poems written in Middle English, I’m always astonished when I come across texts that make links to real events – especially acts of atrocity – that have happened in my living memory; I imagine, with discomfort, what literature students will be saying about such ‘ancient history’ in 50 or 100 years’ time. In this case, reminiscent of the 7/7 London suicide attacks in 2005 that killed 52 people, Pitcher’s characters live in the aftermath of a terrorist bombing in London which resulted in 62 casualties, including Rose, the sister of the young protagonist, Jamie.

Unsurprisingly, this trauma tears Jamie’s family apart: his parents split up, he moves with his Dad and remaining sister, Jas (Rose’s twin), to the opposite end of the country, and is confronted again and again by his parents’ grief and neglect. Most devastatingly of all, Jamie is filled with guilt and confusion that he feels no loss; he was, after all, too young to remember his sister or exactly what happened, and his naive attempts to re-fuse his shattered family are all in vain.

Jamie’s bewilderment at what is going on around him is the most powerful emotion in this book; having moved away from London to the Lake District, he has lost everything he once relied on. What is more, he seems to have no hope of establishing a stable sense of belonging within his new home or his new school due to his complete inability to relate to the one event that defines his devastated family: Rose’s death. He is forever desperate to connect in some way to the girl he is supposed to be mourning, but the only memory he has fills him with self-loathing for its vagueness: the image of “two girls on holiday playing Jump the Wave, but I don’t know where we were, or what Rose said, or if she enjoyed the game” (7).

Ironically, while Jamie feels lost, there is huge importance attributed to the ‘right place’ for the dead Rose. The very title of the book establishes Rose’s ashes as belonging in her urn “on the mantelpiece” and Jamie’s father effectively keeps this area as a shrine to his daughter, providing her with food and drink, Christmas presents and a constant supply of kisses, so that the hallowed ground fills 10-year-old Jamie with fear. When the family is in the car, Jamie notices that “Dad even put a seat belt around the urn but forgot to tell me about mine” (44). Jamie’s fear that he doesn’t belong in his family home, and that he is “five steps” away from “disappear[ing] out of sight” (71) altogether, is only exacerbated by the difference he sees between his father’s treatment of him and his dead sister who is always, literally and figuratively, in “a better place” (6).

In fact, Pitcher demonstrates that the only way Jamie can come to terms with his new living situation, in the north of England, is to measure it repeatedly against his old home in London, which is “so different […] the complete opposite” (3). In contrast to the capital city, to which it is much “too far to drive” (26), there are “no people” (3) in Ambleside and “no buses or trains if Dad’s too drunk to go out” (9). Even when the findings are positive – Cumbria has “twisty lane[s]” (3) instead of “main road[s]” and the “gurgle gurgle” (26) of streams instead of the constant sound, sight and smell of traffic – Jamie finds it hard to let go of the comparisons with his London background. Although the North-South divide is not presented as tangibly in this novel as in David Almond’s The Fire Eaters, it is clearly a massive issue for young Jamie, who finds it hard to settle in between the “massive mountains” (3) that make everything else seem insignificant.

Differing concepts of what it means to be “British” (26) also come under fire in this novel, although it is not the most advanced part of the plot. For Jamie’s dad, being British and being Muslim are shown to be mutually exclusive; his grudge against the Islamic extremists that were responsible for his daughter’s death extends to all reaches of the Muslim faith, without exception. For him, the north of England epitomises “real” Britishness, where white Christian people go about their daily business, surrounded by rolling hills and beautiful views, far away from any of “that foreign stuff” (26) associated with life in London. The irony is (as Jamie soon realises) that his drunkenness, neglect and broken family are further outside his ridiculous ‘British’ standards than any characteristic Sunya portrays: she has “lived in the Lake District all her life” as part of a respectable family, with a “brother at Oxford University” (73), traits that Pitcher seems to suggest are stereotypically British. I am not wholly convinced by Pitcher’s brief treatment of ‘Britishness’ in the novel – she seems to adhere to as many stereotypes as she breaks – but she also manages to present this confusion as part and parcel of life in modern England, which makes it an important theme of the novel.

The true brilliance of this book, and something that it shares with The Fire-Eaters, is the way all of this is narrated, believably and artfully, through a child’s perspective. Although I am sometimes skeptical of this technique (it can be overused), the depth of the subject matter versus the simplicity of the child’s understanding is a winning combination in Pitcher’s case, and deserves a 4/5 star rating. It is also a pleasant surprise – literally speaking – to find a children’s novel that also results in an intentionally untidy and not-wholly-happy ending. Due to all the unanswered questions and loose strands, I would not call this, as some have, a Bildungsroman, but Jamie does at least come to the satisfying realisation that the only thing that makes a house a home is the (living) people within its walls, even if all Jas has to do is “put a cushion” (5) on the windowsill to be the best sister in the world.

Next week I’ll be reading Bryan Talbot’s Alice in Sunderland for Tyne and Wear. Let me know what you thought of this one before I get stuck in!